The Mosaic Apse of Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna:

A Miracle in Design

Aidan Hart

Sant’Apollinare in Classe mosaic. Apse 6th century, triumphal arch 7th -12th century. Photo by Steven Zucker.

There is some iconography that can only be described as miraculous. Such is the sixth century apse mosaic at the basilica of Saint Apollinare in Classe, five miles from Ravenna, Italy. Such works seem to flash forth, and are never – perhaps can never be – repeated. They delight the beholder immediately but at the same time possess layer upon layer of meaning, which reveal themselves only to the patient. In this article I would like to discuss some of these layers.

The Image

Imagine a verdant garden. It embraces you. Its emerald green does not just reflect light; it emanates light. To this paradise add animals, trees, birds, and a saint. This haloed saint stands in the midst of the garden, with his hands raised in prayer.

Above him is a great golden cross set within in an orb of star speckled blue. At its heart is a medallion bearing an image of Christ. This orb, encircled with a jewel-studded crown, hovers within a sky of gold and sunrise coloured clouds. Two saints are set in this golden sea, pointing to Christ. A divine hand reaches down from the summit of the semi-dome. All this fecundity is finally embraced and contained by a broad arch of foliage that supports a host of birds, singing no doubt.

And there are still more laid out on the triumphal arch and in the curved apsidal wall below. But we shall come to these later.

What does all this imagery mean? It is in fact a depiction of the Transfiguration of Christ, as described in the Gospel accounts of Matthew 17:1-8, Mark 9:2-8 and, most fully, in Luke 9:28-36. And the wonderful thing is that this mosaic depicts not just the event, but also the meaning of the event – its many meanings. The mosaic is a profound theological discourse.

But this visual discourse is not merely to be observed. It is enacted in the Holy Liturgy that is performed within its embrace, for the mosaic is in an apse and therefore surrounds the sanctuary and Holy Table. It is here, during the Holy Liturgy, that the Holy Spirit descends and makes the bread the Body of Christ, and the wine His Blood. Before this apse the faithful participate in the divine feast and are themselves transfigured into the body of Christ. As we shall see, the mosaic unveils for us the cosmic significance of the Liturgy for which it is a setting.

In this article I want to explore some of the themes expressed by this splendid mosaic. Some of these themes were without doubt intended by the designer. Others may or may not have been. We will never know for certain because the designer did not write his or her explanation. But, as we shall see, these themes are nevertheless theologically implicit because the mosaic explicitly links the Transfiguration with the Holy Liturgy and the Lord’s Second Coming.

The Eucharist

The Transfiguration event

Moses

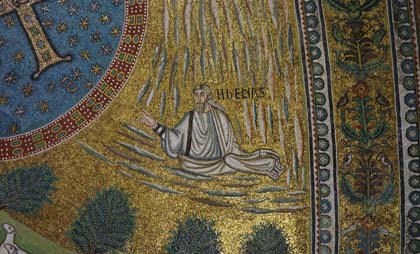

Elias/Elijah. Photo by Steven Zucker

How do we know that this mosaic depicts the Transfiguration? The main clue is the two figures set in the sky. They are labelled Moses and Elijah (“MOYSES” and “HbELYAS” to be precise), and it is they who appeared with Christ during the Transfiguration. Also, on either side of the great jewelled cross are three sheep. They represent Peter, James and John whom Christ took onto mount Tabor to witness His transformation. The brightly coloured clouds suggest “the bright cloud” that overshadowed them. The hand above would therefore indicate the voice of the Father, saying, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to Him” (Matthew 17:5).

A hand symbolizing the voice of the Father

So much for the mosaic’s similarities with the Gospel accounts. But what of its many differences? Why, we might ask, is Christ depicted so small, and in the midst of a great cross instead of in His shining garments? Why the stars, and why are the clouds coloured? And instead of the mountain of Tabor we have a garden. And Bishop Apollinare was not present in the Transfiguration, so why does he figure so large in the depiction?

These and other anomalies immediately invite us on a journey to try and discover their meaning. My first encounter with this mosaic I can best liken to smelling a host of fragrances that had drifted over the wall of a concealed garden. These delighted my senses, but at the same time inflamed my curiosity to find their source and to enter their garden.

Past, present and future

The secret to this mosaic lies in the fact that it depicts not merely the past, but also the present and the future. It is set in divine time, in kairos, where past, present and future exist together in Christ. More specifically, the apse depicts not just the historical event of Christ’s Transfiguration, but also the present Eucharist and the Kingdom that is to come. It is as much an icon of the Parousia and the Liturgy as it is of the Transfiguration. It is at once historical, liturgical and eschatological (a fancy word which means the study of the end times).

Because this image is so multivalenced I think the simplest approach is to work verse by verse through Luke’s description of the Transfiguration and see how the mosaic interprets his words.

The Cross: Christ’s Second Coming in glory

The jewelled Cross, sign of Christ’s transfiguration, crucifixion and Second Coming

Whoever is ashamed of me and my words, the Son of Man will be ashamed of them when he comes in his glory and in the glory of the Father and of the holy angels.

‘Truly I tell you, some who are standing here will not taste death before they see the kingdom of God.’

About eight days after Jesus said this, he took Peter, John and James with him and went up onto a mountain to pray.

(Luke 9:26-28)

One key to the deeper meaning of our mosaic is given in fact some days before the event of the Transfiguration itself. Luke tells us that eight days before His Transfiguration (Matthew and Mark say six), Christ spoke to His disciples of His Second Coming, saying that He would come in His glory and in the glory of the Father and of the holy angels.

In the Gospel of Matthew Christ tells us that at His coming again “there will appear the sign of the Son of Man in heaven” (Matthew 24:30). This sign of the Son of Man has been understood by the Church Fathers to be the cross.

So the cross in our mosaic is the sign of the Son of Man that will appear in the heavens in the last days, a sign of His Second Coming. Both the mosaic and the synoptic Gospel accounts affirm that the Transfiguration was in fact a foretaste given to the three apostles - and to us – of His coming again in glory to establish His Kingdom without end.

The eighth day

Luke’s mention of eight days is a further affirmation of this interpretation. God created the world in six days, and rested on the seventh. Christ died on the sixth day, “rested” in the tomb on the seventh, and rose on the eighth day. The eighth day resurrection therefore takes human nature beyond the endless trapped cycle of the seven day week. In so doing, Christ raised up the created and fallen human life that He had assumed (the six days of creation), so that it could participate in divine and eternal life (the eighth day). Eight is thus a symbol of the created world assumed into the divine life, in a union without confusion. The Father has raised us up with Christ and made us sit with Him in heavenly places.

Another clue to this link between the Lord’s Transfiguration and His Second Coming is His other statement, eight days before the Transfiguration: “Truly I tell you, some who are standing here will not taste death before they see the kingdom of God”. The immediate meaning of these words is understood by most commentators to refer to Christ’s coming Transfiguration. The “some who stand here” are Peter, James and John. Simultaneously this sentence can be read as an oblique reference to His Second Coming. The Gospel of Matthew makes very clear the connection between the Taboric experience and the Second Coming when he writes: “Truly, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom” (Matthew 16:28). The phrase “Son of Man coming in his Kingdom” is often used to describe Christ’s Second Coming at the end of the age.

The stars

In Christian art stars usually symbolize angels. So the many golden stars in the orb that surrounds our cross represent the host of angels who will accompany Christ at His Second Coming.

There are in fact ninety-nine stars in our mosaic. Is this precise number significant? Christ’s parable of the lost sheep (Matthew 18:10-14) speaks of the shepherd leaving ninety-nine of his flock to find the one lost sheep. Collectively we are that lost sheep, and the good angels are the ninety-nine sheep not lost. So these stars are effectively the cloud of heavenly hosts who will accompany Christ at His Parousia.

The number ninety-nine appears again in the Bible and offers a second, complementary layer of meaning. In Genesis 17:1 we read that this was Abraham’s age when God appeared to him and gave His covenant to make him the father of many nations. God promised: “I will establish my covenant as an everlasting covenant between me and you and your descendants after you for the generations to come, to be your God and the God of your descendants after you” (Genesis 17:7).

The number eight arises again in this context, linking the Abrahamic covenant with the Transfiguration and Resurrection: God commands the Israelites to circumcise all their males eight days after their birth (17:12). As with the eighth day Resurrection, the child’s eighth day circumcision is the first day of his everlasting membership of God’s community.

So our mosaic suggests a link between this promise to Abraham and the kingdom to come, in which the faithful from many nations are gathered into the New Jerusalem, the kingdom of God, to live in an everlasting covenant with Christ.

That this is a valid interpretation of the ninety-nine stars is affirmed by the inclusion of Abraham in a mosaic panel on the south wall of the apse. It depicts the priest King Melchezidek standing behind an altar with bread and wine, with Abel offering a lamb on his right, and Abraham offering Isaac on his left.

Our mosaic develops this theme of priestly offering still further, but we shall discuss this a bit later.

The garden and the mountain

They “went up onto a mountain to pray”. Mountains are where people meet God. We think of Mount Sinai in particular, where Moses met the Lord. But our mosaic gives no indication of such a mountain. In fact it replaces the mountain with a garden, a paradise.

The paradise garden

Our mosaic seems to be saying that the Transfiguration transports us humans back to paradise, our original home where we were intended to meet and commune with God. It is a place of intimacy, a place to dwell and enjoy.

People visit mountaintops, but they do not stay there. A mountaintop is a place of ecstasy, from which we eventually have to descend. After he had communed with God and received the tablets of the law on Sinai, Moses had to leave the summit and descend back to the encamped Israelites. Likewise, Christ returned to the world with His three disciples after His Transfiguration. Mountains are not a place of instasy and a place to remain, but gardens can be.

In this context it is worthwhile tracing the development of the word paradise, since the many associations it has accrued over time are present in our mosaic. The word began as an old Iranian word, paridayda, and signified a walled enclosure. By the 6th century BC the Assyrian’s had adopted it as pardesu, domain. For the Persians it came to refer to their expansive walled gardens. For the Greeks it became paradeisos, a “park for animals”. In Aramaic it explicitly refers to a royal park.

Finally, paradise came to be equated with Eden through the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. The Septuagint translates the Hebrew term gan גן or garden (Genesis 2:8 and Ezekiel 28:13) with the Greek word paradeisos. So the garden of Eden becomes paradise. There, according to the Genesis account, God placed us humans and give us the task to cultivate it. There He walks and talks with us.

So we are now in a place to gather together all these connotations of the term paradise and relate them to our mosaic. A paradise is a secure enclosure, with the suggestion therefore of permanence; it is a domain, a kingdom; it is a large garden or park; it includes animals; it is a royal park, where the king and queen enjoy the company of their family and friends; and it is a place where God has placed us and given us a task. It is where we are in intimate communion with God.

Our mosaic reflects all these associations. In turn:

The border of paradise

- Enclosure. The mosaic possesses various concentric bands of enclosure. Firstly, the apsidal dome mosaic is bounded by a broad decorative band. Secondly, the curvature of the apse itself is a form of enclosure. Thirdly, on the verticals of the triumphal arch either side of the apse are depicted Archangels Michael and Gabriel.

Archangels Michael

Archangel Gabriel

They are angelic warriors sent to war against demonic enemies and protect the world and the Church. And finally, the walls of the whole basilica would have been another level of enclosure since originally the basilica would have been – or at least have intended to be - full of mosaic, thus making its whole interior a garden. As St Irenaeus (died c. 202 AD) tells us, “The Church has been planted as a paradise in this world”.

- Permanence. The Lord’s Second Coming will establish His Kingdom without end. And there is something about this mosaic that gives a sense of completion, wholeness, permanence. And yet it also possesses dynamism, movement and life. Once senses an affirmation of St Paul’s (and St Gregory of Nyssa’s) assurances that even in eternity we shall continue to grow in His likeness, passing from “glory to glory” (2 Corinthians 3:18). Eternity’s permanence will not be static but dynamic.

Christ the King and Logos. Upper tier

- A kingdom. In a medallion at the very top and centre of the triumphal arch is depicted Christ, blessing and holding the scriptures. He is the Logos, the creator and guider of His kingdom below. Every ministry that Bishops, priests and lay possess is in fact a participation in Christ’s ministry. As Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has written, One is priest (Christ); some are priests (the ordained clergy); all are priests (the laity). Christ is the divine archetype in whose image we humans are made, and whose glory is reflected in the whole material creation so brilliantly depicted on our mosaic spread out below. The priesthood and regal role of Saint Apollinare depicted below is a participation in the priesthood and kingship of the Archpriest and King of kings depicted above.

Detail from a garden

A detail from Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, to show

the brilliance of the smalti colours

- A large park. Photos cannot do justice to this mosaic. When one sees it in the flesh it seems both vast and verdant. Including the triumphal arch, the mosaic measures about 14 metres/46 feet across and 15.5 metres/51 feet high. But the curvature of the apse means that the actual running dimensions of the apse are greater still: around 24 metres/78 feet wide, and 17 metres/55 feet high. So much for the impressive size. Add to this the emerald green and you feel embraced by the garden. The great meadow of luminescent green mingles with blue and gold, adorned with imperial reds. Set against this deep expanse the whiteness of the sheep and the saints’ garments seem brighter still.

Creatures in paradise

- Animals. Creatures in paradise We see sheep, but also birds perched on trees, rocks, grass, and even on the floral adornment of the border. The sheep of course represent the human flock of Christ. But they are surely there also, along with the birds, to remind us that all creatures are created by God and are thus part of His kingdom. Together with the rocks and the trees this mosaic represents all three kingdoms: the mineral, vegetable and animal realms. Material creation plays an essential role in or union with God. As St Irenaeus reminds us, “the initial step for us all to come to knowledge of God is contemplation of nature.

Saint Apollinare

- A royal park. This mosaic suggests not just a park, but a royal park. Saint Apollinare’s chasuble is purple. Purple cloth was an imperial monopoly in Byzantium and therefore represents royalty. Apollinare stands in the midst of his park as a prince ruling under the King of kings, surrounded as it were by family, friends and members of the court. So as well as depicting Apollinare as a celebrating bishop, our mosaic also suggests his - and by extension, our – role as kings and queens within the world.

- The Edenic task. The creation account in Genesis (2:15) tells us that “The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it”. We had work to do in paradise. St Irenaeus reminds us that though Adam and Eve were sinless before the fall they were not yet perfect. They had a God-given task, and this task once fulfilled would lead to their perfection, which was union with God, transfiguration.

We were made in the image of God, but had the task to grow in His likeness through love for and obedience to Him. Irenaeus reminds us that “Man is created in the image of God [i.e. the Father], and the image of God is the Son, in whose image man was created. For this reason the Son also appeared in the fullness of time to show how the copy resembles Him.”[1]

The Transfiguration of Christ

The face of Christ

As he was praying, the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning.

(Luke 9:29)

Ironically, this mosaic of the Transfiguration does not depict the transfigured Christ, or at least, not His full figure clothed in brilliant white as is usually the case. We have instead the cross, with Christ’s face set in a small medallion at its centre, and the large figure of Saint Apollinare. We have already discussed how the cross represents Christ’s Second Coming, of which His transfiguration is a foretaste. But we can delve deeper still into our mosaic’s other layers of meaning.

Our mosaic concentrates not so much on the event as on its outcome, its purpose. The ultimate purpose of Christ’s incarnation is our deification, our union with Him. As St Athanasius, wrote, “God became man, that we might become gods” (On the Incarnation, 54:3). And St Iranaeus: “Because of his boundless love, Jesus became what we are that he might make us to be what he is” (Against Heresies, V).

So what our mosaic concentrates on is not so much Christ’s transfiguration as ours. St Apollinare himself is clothed in a brilliant white dalmatic under his chasuble. The sheep are also of course white, and stand out particularly against the green. And we have also the white garments of Moses and Elijah, which, standing as they do against a golden background, appear not quite so brilliant as the sheep. It is as though Christ were stepping back a little in order to bring our transfigured state to the fore. This is the same principle He applies when He tells the disciples that He must depart this world so that He can send them the Holy Spirit. Through the Spirit dwelling within them and transfiguring them He will be closer than if He were present only in the flesh as a human individual.

It was not in fact not surprising that Christ shone with light, for He is the glory of the Father, light from light, true God from true God. The unusual thing was rather that He hid His glory for most of the time while on earth. He did not want to overwhelm and compel our freedom. Why then did He allow His glory to shine in this particular instance, on Mount Tabor? One reason is suggested by an Orthodox liturgical text: He wanted not only to display His divinity, but also to show us what it is to be fully human:

’I am he who is’,, was transfigured today upon Mount Tabor before the disciples; and in His own person He showed them the nature of man, arrayed in the original beauty of the Image.

(The Feast of the Transfiguration, Great Vespers, Aposticha)

Some of the Church Fathers say that Adam and Eve were in fact clothed with light before the fall, and only became naked when they turned from God’s ways. Christ’s transfiguration therefore indicates a return to this “natural supernatural” state of the human person. He wants to show His disciples the purpose and end of His work a few days before His crucifixion.

Moses and Elijah

Two men, Moses and Elijah, appeared in glorious splendour, talking with Jesus. They spoke about his departure, which he was about to bring to fulfilment at Jerusalem.

(Luke 9:30-31)

Moses and Elijah are depicted plainly either side of the cross. They are the only human figures in our mosaic that are clothed entirely in white. Luke tells us that they were speaking about Christ’s departure about to be fulfilled in Jerusalem. This is usually taken to refer primarily to His crucifixion, but I would suggest that at the same time it refers to His Ascension, His departure from earth into heaven.

As we have discussed, our mosaic concentrates on the purpose of events in Christ’s life, and not just the events themselves. Thus the cross in our mosaic is golden and jewelled, to show that it is not only the instrument of the crucifixion but also the sign of conquest and transformation, the means by which Christ tramples down death by death.

But I would suggest that our cross also suggests the Ascension, or rather the words of the angels accompanying the Ascension: “‘Men of Galilee,’ they said, ‘why do you stand here looking into the sky? This same Jesus, who has been taken from you into heaven, will come back in the same way you have seen him go into heaven”’ (Acts 1:11). In other words, His second coming will be like His Ascension, with a cloud of witnesses (the stars), accompanied by the sign of the Son of Man (the cross).

The Alpha and Omega

Either side of the cross’s arms are the Greek letters Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the alphabet. These two simple letters capitulate the whole theme of the apse mosaic. The mosaic aims to encompass not just the beginning but also the end, the fulfilment of God’s work of salvation in Christ. Hence we find below the cross also the Latin words, Salus Mundi, “the salvation of the world”. And above the cross is the Greek word for fish, ΙΧΘΥΣ, the famous acrostic formed by the initials of five Greek words meaning “Jesus Christ, Son of God, the Saviour”.

Jerusalem and Bethlehem

This theme of beginning and end is further alluded to by the depiction (executed in the 7th century) of Jerusalem and Bethlehem atop the triumphal arch. Six sheep come out of each gate towards Christ who is depicted in the centre. Bethlehem, His birthplace, represents the beginning of Christ’s earthly ministry, while Jerusalem represents the fulfilment of it. Some commentators also interpret these two holy places as representing respectively the Jews and the Gentiles, who come together in the Church.

Jerusalem and Bethlehem

The clouds

Peter and his companions were very sleepy, but when they became fully awake, they saw his glory and the two men standing with him. As the men were leaving Jesus, Peter said to him, ‘Master, it is good for us to be here. Let us put up three shelters – one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.’ (He did not know what he was saying.)

While he was speaking, a cloud appeared and covered them, and they were afraid as they entered the cloud.

(Luke 9: 32-34)

In our mosaic we find coloured clouds both in the apse and on the uppermost register (executed in the 9th century) atop the triumphal arch. Such sunrise type clouds are common in apsidal mosaics in Rome. They are generally taken to indicate Christ’s Second Coming, for He will come like the sun rising.

The hand of blessing

A voice came from the cloud, saying, ‘This is my Son, whom I have chosen; listen to him.’ When the voice had spoken, they found that Jesus was alone. The disciples kept this to themselves and did not tell anyone at that time what they had seen.

Luke 9:35,36

God the Father ought not be depicted, for He was not incarnate. But here His voice is suggested by the presence of a hand reaching down from the golden heavens. This makes the apse trinitarian, if one takes the gold background and the white to suggest the presence of the Holy Spirit.

Saint Apollinare, priest of all creation

How are we to understand the large figure of Saint Apollinare (identified by the inscription “SANCTVS APOLENARIS”)? We could say that he is there simply because he was the first bishop of Ravenna. But everything about this apse suggests a schema extremely well thought out and multivalenced. The way that the holy bishop and martyr is set within the scene suggests that he has a broader significance.

Bishop Apollinare is celebrating the liturgy. The twelve lambs beside him represent all the faithful, and the garden around him is a microcosm of the whole creation that he and all the faithful offer in the Eucharist, and upon which the Holy Spirit descends and transforms.

But I would suggest that Saint Apollinare, as well as being an individual person, a bishop and a saint, also represents the whole Church in her Eucharistic fullness, giving thanks for and offering all creation. His hands are raised in the orans gesture. This is a sign of intercession and, most critically, the gesture used by the presiding bishop or priest at the epiclesis when, on behalf of all the faithful, he asks the Holy Spirit to “come down upon us and these gifts here spread forth”.

Yellow or deeper green tesserae surround each created thing

The Church is a priestly being, whose calling is to give thanks for all creation and to offer it to the Creator. The Creator in His turn transfigures and offers this world back to us. The Scriptures after all end in the city of God coming down out of heaven to earth, radiant in its fullness, for “the glory of God gives it light, and the Lamb is its lamp” (Rev. 21:23).

The mosaic gives us adumbrations of this cosmic transfiguration. Being a human person capable of a relationship with the living God, Saint Apollinare has a halo of gold. But the rest of the cosmos is nevertheless also capable of participating in God’s glory, each thing according to its capacity. So in our mosaic we see trees, rocks and sheep surrounded by an aura of either yellow or rich green tesserae. We recall that not only did Christ’s person shine with light on Tabor, but also His inanimate garments. Through incorporation into the Body of Christ and through our Eucharistic life, all matter can be transfigured. Through us the cosmos can become garment and adornment for the Body of Christ.

I have the privilege of possessing a few of the original sixth century tesserae from this mosaic, given me by one of the restorers who worked on it in the 1970’s. I am a mosaicist myself, and have noticed that these smalti glass tesserae, especially the green ones, are somewhat more translucent than modern smalti. This in part explains the special luminosity of our mosaic. Sunlight enters each piece and re-emerges as emerald tinted. Light thereby literally comes from within the mosaic itself, and is not merely reflected off its surface. We are witnessing the material word shining with light, like Christ’s garment on Mount Tabor.

The lower tier with bishops of Ravenna

The fellowship of the saints

Below Saint Apollinare, set between the windows, are mosaics of four previous bishops of Ravenna: Ecclesius (ECLESIVS), who was bishop of Ravenna from 522 to 532 and founder of San Vitale; Severus (SCS SEVERVS), a revered bishop of Ravenna in the 340’s; Ursus (SCS VRSVS), bishop ca. 405-431 and builder of Ravenna’s cathedral and baptistery; and Ursicinus (VRSISINVS), bishop 533 -536, and commissioner of Sant’Apollinare in Classe.

These bishops, together with Saint Apollinare (the first bishop of Ravenna), serve to locate within the apostolic succession each priest who celebrates in the basilica. By association they also set everyone who worships in the basilica within the fellowship of all believers, past, present and future. The union that this mosaic affirms is not just between God and man and matter, but also between the all faithful throughout time.

On bees, work, kings and gardens

Quite remarkably, close inspection of the little golden designs on Saint Apollinare’s chasuble reveals that they are in fact bees. In Christian symbolism bees represent the immortality of the soul and the resurrection (for a hive seems to come back from the dead after three months of winter hibernation).

But bees also represent communal transformative labour, since the work of the hive changes nectar into honey. This is graphically affirmed by two passages in the ancient hymn Exsultet, sung in the Western Church by a deacon in front of the Paschal candle. This hymn was composed perhaps as early as the fifth century, and certainly no later than the seventh, so it may well have been known by the person who designed the mosaic and therefore support this interpretation of the bees on Apollinare’s chasuble. The passage reads:

O holy Father,

accept this candle, a solemn offering,

the work of bees and of your servants’ hands,

an evening sacrifice of praise,

this gift from your most holy Church.

But now we know the praises of this pillar,

which glowing fire ignites for God's honour,

a fire into many flames divided,

yet never dimmed by sharing of its light,

for it is fed by melting wax,

drawn out by mother bees

to build a torch so precious.[2]

So this hymn traces the stages from God-given nectar, to the work bees transforming nectar into honey and wax, followed by man’s work to change the wax into candle. All is culminated in the material wax becoming immaterial fire in praise of God. The process of labour is thus completed in transfiguration, a living light that knows no diminution in its sharing.

As kings as well as priests, we are called not just to give thanks for all creation, but also to work within it to transform it like bees. Or to use another analogy, as spiritual gardeners we are to cultivate the wild and wonderful world into a garden.

The Lord’s command to Adam and Eve to “fill the earth and subdue it” (Genesis 1:28) needs to be understood in just this transformative sense. Our God-given power within the world is, I think, best understood in an artistic sense rather than exploitative. The artist’s power over his or her medium is that of craft and wisdom (Minerva the Roman god of wisdom was pertinently also the good of crafts). The wise artist or craftsperson uses their power over the medium with love and discernment, to raise the raw material into something even more beautiful. Their authority therefore exists not to subjugate and oppress their medium, but to raise it up and make it even more articulate.

It is clear from their branch collars that the larger trees in the mosaic have been pruned. We are clearly looking not at a wild forest but a garden, one cared for by men and women. Our bishop Apollinare is a spiritual gardener as well as a priest. So the garden around Apollinare is the outcome of love and craft, and of God and man working together in synergy.

Sometimes in the Gospel narratives people blurt out things that appear to be mistakes but end up being prophetical. Such is the case when Mary Magdalene mistakes the risen Christ for a gardener:

Jesus said to her, “Woman, why are you weeping? Whom do you seek?” Supposing him to be the gardener, she said to him, “Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away.”

(John 20:15)

Christ is the second Adam, who becomes and fulfils all that the first Adam (that is, us) failed to be and do. In this case, He has become the Gardener in Eden. It is interesting to contrast this scene with that in Genesis. In Genesis Adam and Eve try to hide from God in Eden. Here in John’s Gospel, Mary Magdalene is trying to find God.

Our mosaic garden has a pleasing blend of orderliness and variation. The highest trees are arranged in a row along the top, at a similar distance from each other but not precisely so, and each is a little different from the others. The shrubs, rocks and flowering plants are likewise arranged, with a perfect imperfection.

This reminds me of something that Saint Paissius of the Holy Mountain once said to me. When modern man makes streetlights for the night he places the lampposts precisely the same distances apart and makes each lamp identical in brightness and colour. This mechanical repetition is tiring to our eyes, he said. But when God made the starry lights for the night He varied their size, spacing and colour, and this soothes the soul. Here in our mosaic we see a garden made according to this same divine pattern of a perfect imperfection, with a dynamic and not mechanical symmetry.

In God’s plan this royal and crafting role is inextricably tied to our priestly role, since in the Eucharist we offer not wheat and grapes, but bread and wine, which are the fruit of human labour. To this theme we shall now turn.

Abel, Melchezidek, Abraham and Isaac, 7th century

Abel, Melchizedek and Abraham

On the south wall of the apse is a depiction of the priest king Melchizedek. He stands behind an altar with two loaves and a chalice. Abel the shepherd stands to his right and offers a lamb, and Abraham to his left offers his son Isaac. This is in fact an amalgamation of two mosaics from nearby San Vitale, and was probably made around 670, at the same time as the mosaic on the opposite wall that depicts Constantine IV (668-685). It is however not impossible that it is a remake of an earlier work made at the same time as the conch mosaic, in the sixth century.

This is an appropriate scene, both because of the Holy Liturgy that is celebrated in front of it and because of our mosaic’s priestly and regal theme.

Like the conch mosaic that takes liberties with historical reality in order to reveal the deeper meaning of the event, this mosaic panel also has some interesting additions. Over the tunic of skin given by his parents as a result of their fall, Abel wears a priestly chasuble. This emphasizes the priestly significance of his offering.

Melchizedek’s garment is identical to those worn by high priests Aaron in the third century fresco at Dura-Europos and Caiaphas in the sixth century mosaic in nearby Sant’Apollinare Nuovo. He also wears also a simple crown to denote his regal status as king of Salem. Abraham is also priestly, ready even to offer his own son on the altar. But he also dressed like a Roman senator, his toga bearing the senatorial shoulder to hem stripe. This suggests, as with Melchezidek, a union of priestly and royal ministries.

Aaron with the tabernacle. Dura-Europos, 3rd century

Caiaphas the high priest. Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna6th century

The “Privilegia” mosaic

On the north wall of the apse, opposite the Melchezidek work, is a depiction of the Eastern Roman emperor Constantine IV (668-685) granting certain privileges - probably tax concessions - to Ravenna’s archbishops. The mosaic is very similar to one of Emperor Justinian found in nearby at San Vitale, and is no doubt based on it. Ours is a seventh century work, but of poor quality, probably due to the multiple restorations it has suffered over the centuries.

Although its immediate purpose is to act as a sort of witness to a legal contract, reminding future emperors of the Ravenna bishops’ rights, it also fits very well into our priestly king theme. On the left side are the secular authorities: the emperor and his brothers Heraclius and Tiberius, with a fourth figure holding a ciborium. On the right is Archbishop Reparatus (671-677), receiving from the Emperor the scroll with its promise of privileges. He is accompanied by another bishop (perhaps his predecessor Maurus (642-671), plus a priest in a yellow chasuble and two deacons. Whereas the Melchezidek mosaic opposite combines the roles of priest and king in one person, here the principle is expressed by the, ideally, harmonious relationship between two distinct entities, the state and the Church.

The Privilegia panel, north wall

Emperor Justinian, San Vitale, Ravenna, 6th century

This Privilegia mosaic encapsulates the Orthodox ideal of symphony between Church and state. They are independent, each with boundaries according to their God-given responsibilities, but each also assisting the other to fulfil God’s purpose. This ideal avoids both caeseropapism and papal-caesorism. The Church can prophetically oppose a secular power that acts contrary to God’s commandments, but it can also accept material assistance from it if this genuinely aids the Church’s spiritual work and benefits people’s lives.

Perhaps this is the meaning of the ciborium held by the emperor’s attendant. The altar table, symbolically speaking, is the exclusive prerogative of the Church, but the ciborium protects this altar, and this protection the state can offer through its laws and privileges.

The date palms

Date palms, symbols of paradise, fruitfulness and victory

For the sake of completeness we can mention the date palms that stand either side of the apse. Palms traditionally represent paradise and a fruit bearing life. In Roman times they also represented victory. Their presence confirms the reading of the apse as a paradise, regained by Christ through the victorious cross. One sees such palms in many other Italian mosaics, such as at Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (6th c.), the ceiling mosaic of Arian Baptistery also in Ravenna (5th c.), at Santa Prassede in Rome (9th c.), and in the apse mosaic of Santa Cecilia also in Rome (9th c.).

The upper tier: Christ and the four living creatures

The upper tier. Christ the symbols of the four Evangelists.

Scholars date the uppermost tier of the triumphal arch to the ninth century. In the centre is Christ in a medallion. Each side are the four winged creatures, each holding a Gospel. They symbolize the four evangelists: the eagle is John; the man Matthew, the lion Mark, and the ox Luke.

This tier capitulates all that happens below. The evangelists summarize the whole work of Christ about which they wrote, from His birth through to His Ascension and the sending of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The purpose of His incarnation was to gather all creation into Himself, and in particular to unite our human nature with His own divine nature. For, as St Paul so poetically writes, the Father “raised us up with him, and made us sit with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus” (Ephesians 2:6).

In summary

I think there are few examples of liturgical art that embody such a wide spectrum of Christ’s work as this mosaic at Sant’Apollinare in Classe. It is a precursor to the rich vision that St Maximus the Confessor was to write about a century later, where in Christ the human person becomes both microcosm and mediator, to use Lars Thunberg’s phrase. But the one passage that perhaps best describes this remarkable mosaic is from the Bible:

For [the Father] has made known to us in all wisdom and insight the mystery of His will, according to His purpose which He set forth in Christ as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in Him, things in heaven and things on earth.

(Ephesians 1:9,10)

[1] Saint Irenaeus, quoted in Man and the Incarnation: A Study in “The Biblical Theology of Irenaeus” by Gustaf Wingren. Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2004, page 19.

[2] English translation from the Roman Missal © 2010, International Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation.